San Francisco’s Historic Fear of Heights

While it’s fun and easy to blame tech Bro’s for the Bay Area’s housing crisis, the truth starts decades before most of these millennials were even born! To get a glimpse into the challenges of development in San Francisco, and why there aren’t enough high-rises to accommodate our population, we need only turn the clock back to about 1960.

Up until about 1960, San Francisco planning followed a simple un-written rule: tall buildings belong at the top of hills, accenting their heights while preserving as much light and view for those lower down the hills. When San Francisco was a blue-collar industrial port town, this worked rather easily. Low-rise manufacturing at the Waterfront scaling up to the tallest structures at the top of Nob, Russian, or Rincon Hill to name just a few of our famous hills.

But after World War II ended, San Francisco began it’s transition from a blue-collar industrial production city to a financial services and white-collar city. The change began on the northern end of town (the most expensive land), trickling down to the southern county border over the coming decades. Loss after loss of blue-collar manufacturing and production jobs in the city culminated with the closure of the Hunter’s Point Shipyard and Schlage Lock Factory in the 1980s.

By the late 1950s, previous industrial sites along the waterfront had been closed and these sites were now becoming prime candidates for re-development. Located at the intersection of North Point and Van Ness Avenue, the Fontana Warehouse was once a military barracks, later a storage warehouse, and even a pasta factory for a period of time. Around 1960 it was acquired and the development of two towers, each about 150 feet in height, was proposed.

And what happens next is why San Francisco real estate is very, very, very expensive.

Russian Hill neighbors, led by none other than Casper Weinberger, led the charge against high-rise development and for their existing views with the epithet of “Manhattanization.” While the Russian Hill Improvement association failed to prevent the construction of Fontana East & Fontana West Towers at 1000 & 1050 North Point in Russian Hill, they laid the groundwork for control of San Francisco city planning by unelected neighborhood associations.

San Francisco underwent a major building boom in the 1960s, with Fontana Towers being just one of the many high-rise developments built across the city, particularly in classic north-end neighborhoods like Nob Hill and Russian Hill, and Pacific Heights. To give you an idea of the dramatic growth, here’s a sampling of what went up in the 1960s across the north side of the city:

1961 – Green Hill Tower, 1070 Green, Russian Hill

1961 – The Comstock, 1333 Jones, Nob Hill

1962 – 1080 Chestnut, Russian Hill

1962 – 1200 California St, Nob Hill

1962 – 2200 Pacific, Pacific Heights

1963 – Royal Towers, 1750 Taylor, Russian Hill

1963 – 1170 Sacramento, Nob Hill Towers, Nob Hill

1963 – Pine Terrace, 1001 Pine St, Downtown

1963 – 10 Miller Place, Nob Hill

1964 – Broadway Towers, 1998 Broadway

1964 – Pacifc Heights Towers, 2200 Sacramento, Pacific Heights

1964 – The Summit, 999 Green Russian Hill

1964/1965 – Fontana East & Fontana West at 1000 & 1050 North Point

1966 – Cathedral Hill Tower, 1200 Gough, Van Ness Corridor

1966 – 2040 Franklin, Jackson Towers, Pacific Heights

1970 – Mandarin Tower, 946 Stockton, Chinatown

Prop T 1970

By the approach of 1970, San Francisco reacted with its instinctive love for the underdog. Resistance to high-rise development crystallized into the first major anti-development propositions. In a quest to prevent the Manhattanization of SF and preserve our “unspoiled views,” Prop T was placed on the ballot in 1971. The proposition would have limited building height to 6 stories (72 ft) for the entire city. It was championed by a local dressmaker, feared by anxious developers, and while it ultimately failed to pass, momentum for change was continuing to build.

Prop P 1972

In 1972 high-rise development is on the ballot again, this time as Prop P on the June ballot, with 160′ height limits in downtown areas and 40′ height limits in residential areas. Prop P fails dramatically, with 57% voting no to only 43% yes.

In other cities, two consecutive votes by the citizens against restricting high-rise development would be seen as a clear sign that the residents want more housing in taller buildings. But not in San Francisco.

The Un-appointed Planners

In 1972 the planning commission, filled by Mayoral appointment at that time, did more to seal the fate of San Francisco as an unaffordable city than anything else.

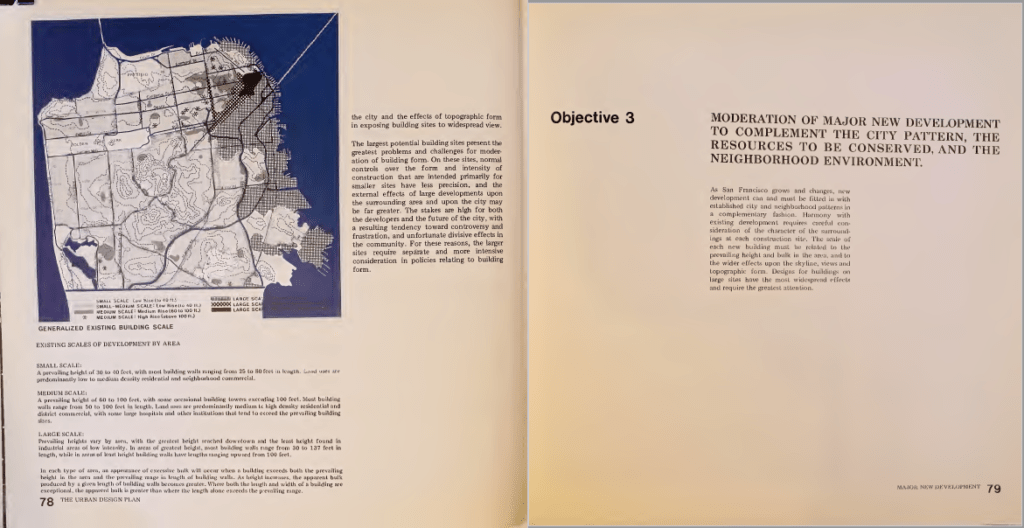

First proposed in May 1971 but not adopted until late 1972, the SF planning commission approved their first “Urban Design Plan” that expressly set a height limit across the city to four stories (40 feet) virtually everywhere but the downtown financial district.

Pages 78 & 79 From SF’s Urban Plan proposed 1971/adopted 1972

Despite two ballot measures in support of high-rise development, the outsize influence of neighborhood associations terrorized the planning department into acquiescing to the demands of the wealthy and white neighborhood associations; associations with political influence and leverage. And thus, with a sledgehammer, SF planning ended debate on what kind of city SF would become with their decision to prioritize light, air and views over affordability.

SF wouldn’t place major housing initiatives on the ballot again until the end of the 1970s when we saw the introduction of rent control on the 1978 ballot and the defeat of downtown height limits in 1979 Prop O. Voters again showed their support for high-rise development by defeating Prop O by a vote of 55% no/45% yes. In 1986, voters narrowly approved Prop M, which limited office space development to 475,000 square feet per year.

Every time the issue is put in front of city voters, San Francisco voters chose growth and development. Neighborhood associations and the planning department were opposed and overrode the popular vote. Even though there was wide public support for more housing in San Francisco, it was stopped by an elite group of unelected officials and citizens

Who were the people that are stopping this? Neighborhood associations. Unelected, self-appointed volunteer members of vocal neighborhood improvement associations were vigorously opposed to development that would impact their light, air, or views. These very vocal neighborhood housing associations opposed to the development of more housing had more power over height limitations than elected city officials or everyone who voted against Prop T, Prop P, and Prop O.

It Didn’t Have to Be Like This

Vancouver

Vancouver is just one of many cities across the globe that proved you can build densely with high-rises on and adjacent to the waterfront and still maintain a beautiful skyline. While other cities advocated for new housing and making room to welcome the future, San Francisco decided to go a different direction and prioritized protecting what had already been built by the early 1970s at the expense of making room for anyone else to arrive and live here affordably.

On our upcoming episode of Escrow Out Loud “San Francisco’s Historic Fear of Heights’, we take a deeper look at all of these limitations, why they are still there, and how we can move on from them. Subscribe to Escrow Out Loud, and be sure to listen to this not-to-be-missed episode.